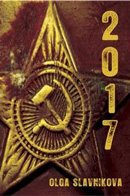

If Olga Slavnikova's novel, 2017, is any indication, the near-future of post-Soviet Russia—and the world in general— looks pretty grim on a variety of fronts, in large part because people of the techno-boom have lost touch with their own history and culture.

As the novel opens, Anfiligov, a successful gem prospector, and his assistant Kolyan are setting off for the fictional Riphean Mountains, poised to find a cache of gems that could make them rich. But the Riphean Mountains are harsh and populated by mythic characters from a mythic folklore. Anfiligov and his assistant are up against forces much larger and more mysterious than they understand.

It's not too hard to see Anfiligov's pursuit of riches as a metaphor for the frustrations Russia has had adjusting from a corrupt communist state to a playground for capitalistic experiments, many of which made Russians yearn for the good old days of the Soviet system. The mysterious Riphean Mountains also seem to be a stand-in for a Russian past that is dimly understood by the Russians themselves after decades of Soviet rewriting of history.

Meanwhile, Anfiligov's mysterious female companion, "Tanya", who sees him off at the train station, begins a chilly affair with Anfiligov's assistant on the home front. Krylov is a former historian now working as a gem cutter, another sign that the old order has crumbled and scrambled social roles as rocks pulled out of the Riphean Mountains are cut and tumbled and remade as gems—gems that must now compete against more perfect, synthetic jewels—in Krylov's shop.

Tanya refuses to tell Krylov her real name or identity, and he plays along as "Ivan"; she agrees to meet him once a week at a spot selected at the end the previous tryst. If one of them fails to show, the affair is over. The pair do fail to meet at a New Year's celebration featuring "maskers" dressed up as White Russians and Bolsheviks, who, unexpectedly begin fighting each other with live ammo. Like re-enactors suddenly gone psycho, several of these "armies" crop up and continue to kill each other—and innocent bystanders—for no apparent reason than the fun of it.

Krylov also has a wife, the svelte and savvy Tamara, whom he has never quite managed to divorce. Tamara is a TV personality, a media darling, with a successful business in the funeral industry. She turns up occasionally to give Krylov lectures—much like the long expositions by O'Brien in Orwell's 1984—on the new world order:

Tamara's lectures are little gems. They're too talky for a conventional novel (which 2017 isn't). But they're great essays.

Overall, 2017 is a mystery without any clear solution, but it opens up layer on layer of interesting ideas. It is dystopian, but contains elements of the absurd, thriller, and magical realism.

In addition, Slavnikova's prose is rife with similes and metaphors—-I counted seven on the first page alone—that

beckon some earnest doctoral student of post-Soviet literature. The cascade of simile and metaphor has the effect of making

even the most concrete images seem insubstantial, nothing is really what it seems, it's more like this. Or that. Or perhaps

something else altogether.

Overlook, hardcover, 9781590203095