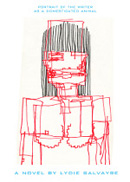

Dalkey Archive, paperback, 9781564785572

This very timely satire pits a ruthless, shrewd, obscenely rich magnate against a young, idealistic writer in a battle for the heart and mind of the reader. If you are thinking that you already know how the battle will turn out, you may be wrong.

When picking up a satirical book, especially one that is translated, I always wonder whether I will understand what the object of the satire is. But the very fact that the book has been translated more than suggests that the satire has universal appeal and so it is with this novel. Salvayre's novel brings to mind contemporary satires, such as Margaret Atwood's Oryx and Crake or much of Victor Pelevin's work. Salvayre succeeds brilliantly at skewering the obscenely rich, the Free Market and the world of finance, the corporate world, and so much more.

Our nameless narrator, a young woman and a cash-poor, idealistic writer, has decided to take a commission to write an authorized biography (known between those involved as "the gospel") of Tobold the Hamburger King, the richest man in the world (who, by the way, has a dog named Dow Jones). To accomplish this, it is decided by Tobold (for he makes all the decisions) that our narrator must be ever present ‒ virtually shackled to the man as he goes about his day. To keep their literary relationship of writer/subject a secret from all but a few of Tobold's closest advisors, she is introduced as his escort and must dress and play the part. Our narrator is soon caught up in a world of opulence, celebrity, and cold-blooded greed, all the while lamenting to herself that she is compromising her principles and is powerless to pull away.

I, who had spent part of my youth at Café des Ormeaux explaining how to fight against Capitalism with thought, I who had always prided myself on being a subversive writer, a writer who violated the rules of syntax, a writer who tore traditional style to pieces, I who had flattered myself on demolishing the idea of the sentence, a terrorist of narration. Progression? Pointless! Endings? Crap! Psychology? Bah! Conventions? Get rid of them! Characters? Old-fashioned ideas from another century! I who considered myself a revolutionary writer—even though that word makes me feel ashamed—a writer dedicated to all rebellions, I didn't dare say a thing that would upset a damn hamburger peddler.

I had to admit it: I was a coward.

Portrait of a Writer as a Domesticated Animal is very witty and sometimes laugh-out-loud funny. The more we learn of

Tobold through the observations of our narrator, the more we recognize the stereotype and find him and

his world ridiculous. And yet, the more our narrator sets herself up as the moral opposite

of Tobold (just as we, the readers, are likely to do), the more thoughtful we are forced to become.

Like Atwood does in Oryx and Crake, Lydie Salvayre has scornfully held modern life up

before us hoping we will join in with the laughter. And laugh we do, until we realize how

complicit we really are.